Choosing the Right Vacuum Gauges: What Most Buyers and Engineers Get Wrong

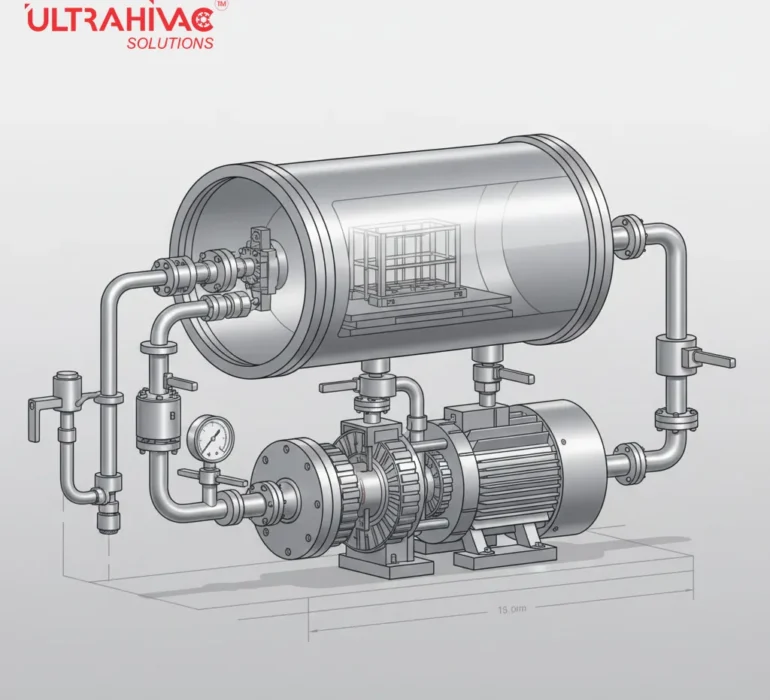

If you have worked around vacuum systems long enough, you start noticing a pattern.

Most systems don’t fail because the pump is weak.

They fail because nobody really understood what was happening inside the chamber.

Pressure readings were wrong.

Gauges were installed in the wrong place.

Controllers were poorly configured.

Warnings were ignored.

And slowly, performance dropped.

This is why vacuum gauges, controllers, and display units are not “accessories.”

They are decision-making tools.

If you get them wrong, everything else suffers.

The Biggest Mistake: Treating All Gauges the Same

Many buyers assume:

“A gauge is a gauge. If it shows pressure, it’s enough.”

In reality, this thinking causes most long-term problems.

Different vacuum ranges need different technologies. Using the wrong gauge is like using a kitchen thermometer in a furnace.

It may show something — but it won’t help you.

Pirani gauges are usually the first ones installed in a system.

They tell you:

When pumping starts

How fast pressure is dropping

When it’s safe to move to high vacuum

In real plants, Pirani gauges are often over-trusted.

They are excellent for rough and medium vacuum, but once you move deeper, their readings become unreliable.

Many systems look “fine” on Pirani — until problems appear later.

Penning gauges come into play when things get serious.

They operate in high vacuum ranges and are far more sensitive to small changes.

In many labs and coating systems, engineers first realize there is a leak only because the Penning gauge doesn’t stabilize.

It’s not dramatic.

It’s subtle.

Pressure takes longer to settle.

Base vacuum is slightly higher.

Process quality drops slowly.

This is how most vacuum issues start.

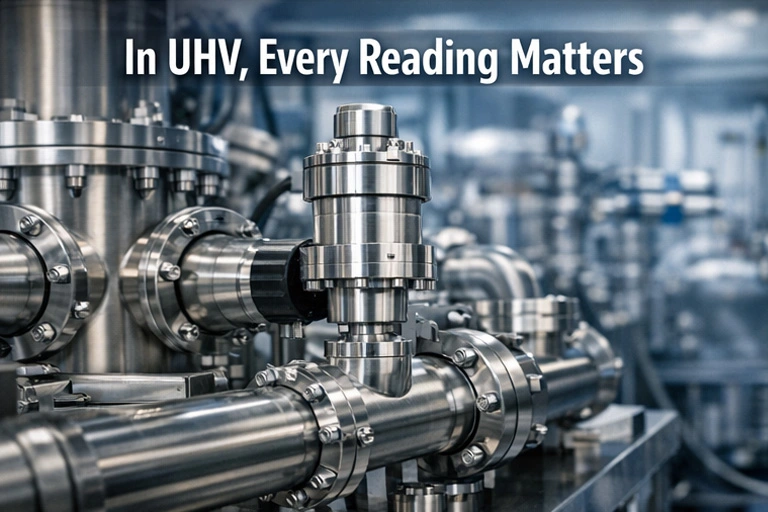

In ultra-high vacuum environments, there is no room for guesswork.

Research labs, semiconductor fabs, and surface science facilities depend on UHV gauges because:

At these levels, even fingerprints, moisture, or tiny material defects matter.

We’ve seen systems where everything looked perfect — except the UHV gauge showed instability.

That single reading saved weeks of wasted experiments.

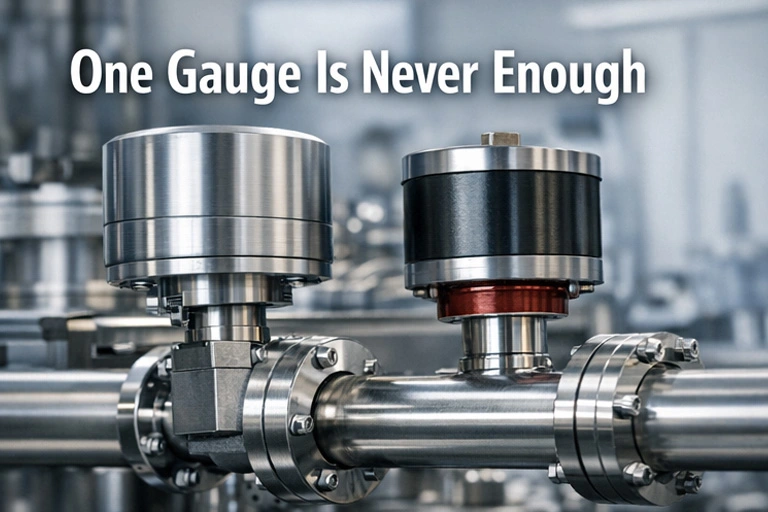

Here’s a hard truth:

Many systems use expensive gauges and cheap controllers.

This is like buying a luxury car and installing a poor-quality dashboard.

Controllers decide:

How signals are processed

When gauges turn on/off

How alarms work

How data is logged

Bad controllers cause:

Signal noise

Wrong switching

False alarms

Operator confusion

Good controllers quietly keep everything stable.

Most failures don’t happen in hardware.

They happen when someone reads the display and makes a wrong decision.

If the display is unclear, badly placed, or confusing, mistakes happen.

Good display units:

Show data clearly

Highlight abnormal values

Reduce reaction time

Improve safety

This matters more than most people realize.

Installation: Where Good Systems Become Bad

We’ve seen perfect gauges give useless data.

Why?

Wrong installation.

Common mistakes:

Mounted too close to pumps

Placed in high gas-flow zones

Exposed to contamination

Poor electrical grounding

One wrong location can make a high-end gauge useless.

How Smart Buyers and Engineers Choose

Experienced teams don’t ask:

“What’s the cheapest gauge?”

They ask:

What range do we really operate in?

What gases are involved?

How stable does this need to be?

How automated is the system?

Who will maintain it?

Then they choose:

Pirani + Penning + UHV (if needed)

Good controller

Clear display

Correct placement

Simple. Effective. Reliable.

Most vacuum problems don’t start with breakdowns.

They start with bad data.

Wrong readings → wrong decisions → slow failures.

If you invest in proper measurement and control from the beginning, your system will reward you with stability, confidence, and long-term performance.

That’s not theory.

That’s experience.