Why Vacuum Levels Deserve More Attention

One of the most common things we hear is:

“We need vacuum for our process.”

That’s a good starting point — but it’s not the full picture.

In reality, vacuum isn’t a single condition. It exists in clearly defined levels, and each level behaves very differently in real industrial environments. Choosing the wrong vacuum range doesn’t just affect performance — it can increase cost, complexity, and long-term maintenance issues.

Understanding vacuum levels helps you make better technical and commercial decisions.

What Do We Mean by a “Vacuum Level”?

Vacuum level simply describes how much gas remains inside a system compared to atmospheric pressure.

It is usually measured in:

mbar

Torr

Pascal (Pa)

As pressure decreases, vacuum quality increases.

But higher vacuum is not automatically better — it only makes sense when the process truly requires it.

The Four Main Vacuum Levels (In Practical Terms)

Low Vacuum – The Starting Point

Low Vacuum – The Starting Point

Typical Range: Atmospheric pressure down to ~1 mbar

Low vacuum is often the first step in most vacuum processes.

It is commonly used for:

Packaging and material handling

Rough evacuation of chambers

Pre-processing before higher vacuum stages

Low vacuum systems are robust, cost-effective, and forgiving. They are designed for reliability rather than extreme precision.

Medium Vacuum – Where Control Begins

Medium Vacuum – Where Control Begins

Typical Range: ~1 mbar to 10⁻³ mbar

This is where vacuum starts influencing process quality.

Medium vacuum is used in:

Industrial drying

Furnaces and heat treatment

Degassing processes

Chemical and process industries

At this level, stability matters more than speed. Leaks, material compatibility, and pump selection begin to play a critical role.

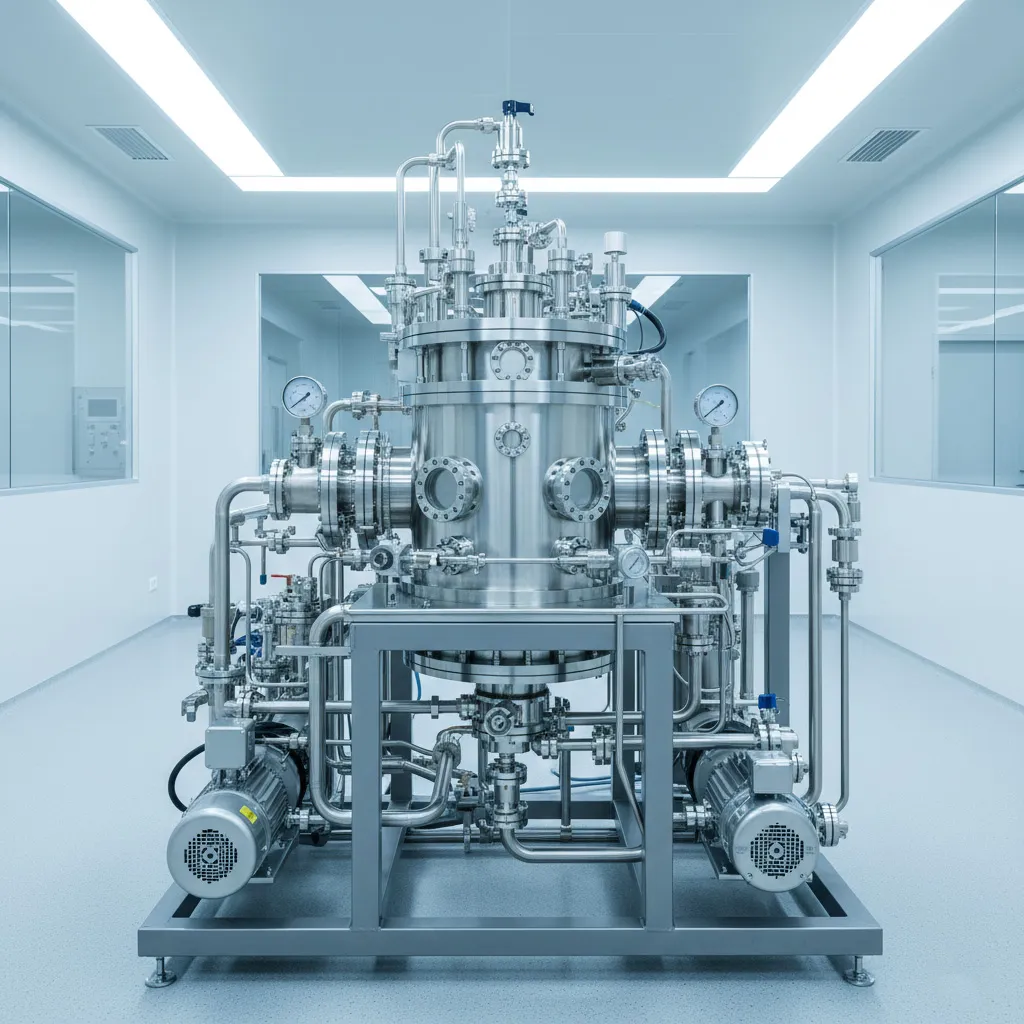

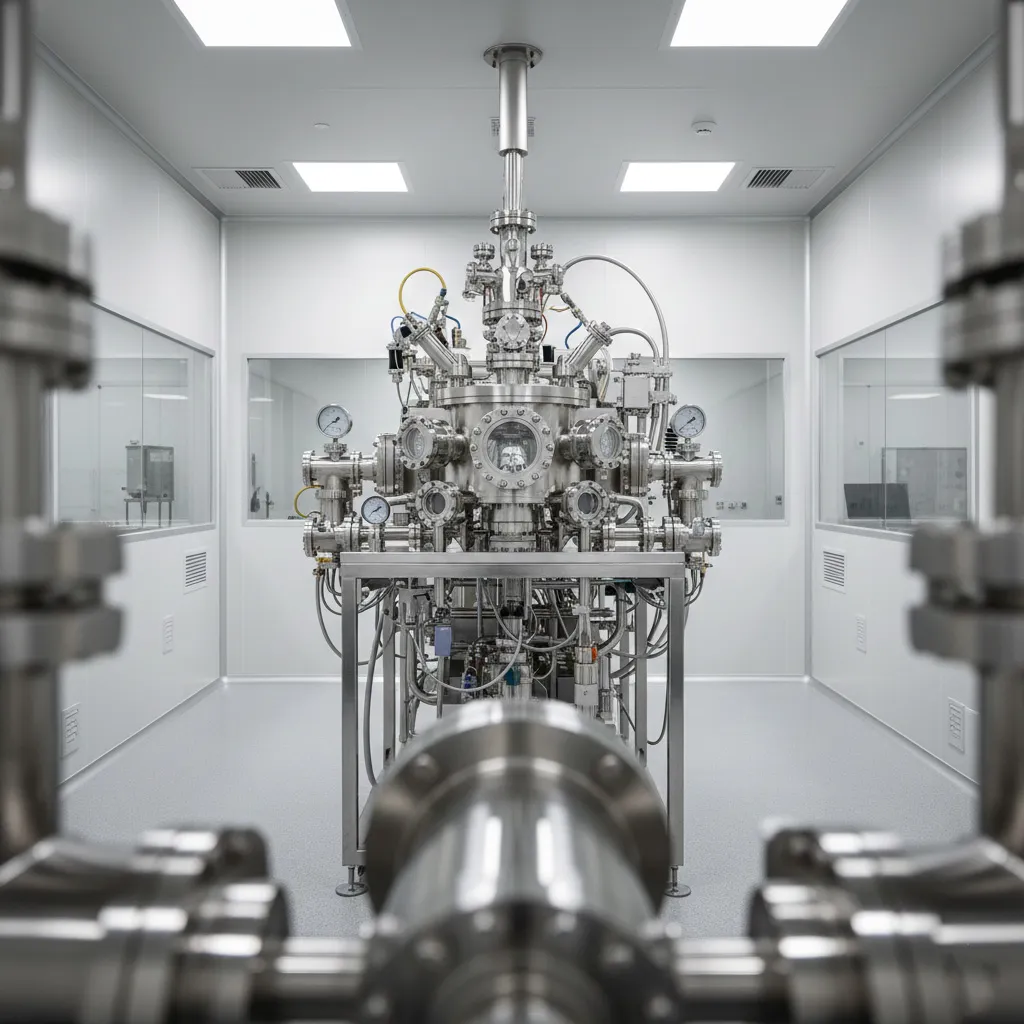

High Vacuum – Precision Territory

High Vacuum – Precision Territory

Typical Range: 10⁻³ mbar to 10⁻⁷ mbar

High vacuum environments dramatically reduce contamination and unwanted reactions.

They are essential for:

Thin-film coating (PVD / CVD)

Electronics and device manufacturing

Analytical and surface-sensitive processes

At high vacuum, system design becomes more refined. Even small issues — like improper seals or poor material choices — can affect performance.

Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV) – No Room for Error

Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV) – No Room for Error

Typical Range: Below 10⁻⁷ mbar

Ultra-high vacuum is used only when absolutely necessary.

Typical applications include:

Semiconductor fabrication

Advanced research and surface science

Space simulation and testing

At UHV levels, everything matters:

Materials

Cleanliness

Outgassing

Assembly practices

UHV systems are engineered environments where microscopic details have macroscopic consequences.

Why “Higher Vacuum” Is Not Always the Right Answer

It’s tempting to think that pushing for the highest possible vacuum will improve results.

In practice:

Higher vacuum increases system cost

Design complexity rises sharply

Maintenance becomes more demanding

The goal is not maximum vacuum — it’s process-appropriate vacuum.

Many processes perform better, more reliably, and more economically at lower vacuum levels.

How to Choose the Right Vacuum Level

The correct vacuum level depends on:

The sensitivity of the process

Materials being handled

Tolerance to contamination

Cycle time requirements

Long-term operating cost

This is why vacuum systems should be designed around applications, not just specifications on a datasheet.

How Ultrahivac Looks at Vacuum Selection

At Ultrahivac, vacuum selection always starts with a simple question:

“What does your process actually need?”

Only after understanding the application do we align:

This approach avoids over-engineering while ensuring reliability.

Low Vacuum – The Starting Point

Low Vacuum – The Starting Point Medium Vacuum – Where Control Begins

Medium Vacuum – Where Control Begins High Vacuum – Precision Territory

High Vacuum – Precision Territory Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV) – No Room for Error

Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV) – No Room for Error

This is a great primer on Vacuum Levels. I agree that the jump from Low Vacuum to Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV) can be confusing for beginners, but your explanation makes it simple. Looking forward to more posts on vacuum science!

Hi LabTech_Intro, thank you for the kind words! We’re glad you found the explanation helpful. Vacuum science can definitely get complex once you reach the UHV range, so we aim to make it as accessible as possible. Stay tuned—we have more technical guides and industry insights coming soon!